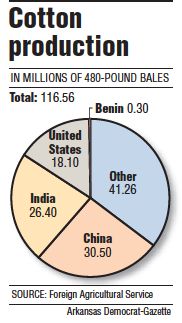

In Tiny Benin, Cotton Is King

Poor nation struggles for a toehold in trade

Each day, Sambo Sero balances his hand-hoe over his shoulder and disappears onto the path that is barely visible from the dirt road. He navigates the twisty route for hundreds of yards in his bare feet, through weeds as tall as he is, passing scattered hardwoods and a field planted in yams.

Sambo Sero grows cotton in Benin on land his family has farmed for generations.Photo: Alex Daniels

Finally he reaches the spot.

Spreading out over 20 acres from the shea tree in the corner where his grandmother is buried, is Sero's big gamble. If the cotton he planted there gets enough but not too much water, and if it fends off the worms and pests, Sero will not only be able to pay for the pesticide, fertilizer and seed that he got on credit, but he'll also be able to feed his family and pocket some cash to put into the field next year.

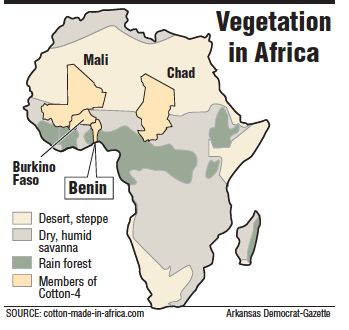

The field is in Benin, a small West African nation where at least 300,000 farmers like himself cultivate plots of cotton, the country's single largest export. Sero's hidden cotton plot is right outside the village of Kalale in northeastern Benin. Near the Nigerian border, the rain-fed savanna soil gets just enough moisture to produce a cotton crop before December's end, when the Harmattan trade winds shift south from the Sahara and the long dry season begins.

For Sero "” a tall, slender 42-year-old man with tattooed markings on his cheeks and a friendly smile "” coaxing cotton out of the ground is a matter of faith, hard work and luck. In that, he's no different from most farmers.

"I planted seeds and expected rain," he said, pausing for a break among some of his 28 children who help out on the farm. "But there was no rain. Then, thanks to Allah, the rain came."

For the past decade "” in places like Qatar, Hong Kong, Geneva and in the U.S. Congress "” trade ministers and lawmakers have struggled to design a policy that helps farmers in poor countries like Benin tap into the wealth of the global commodity trade. They have tried to help farmers like Sero "” who plows, weeds and picks his crop by hand "” compete with farmers in places like Arkansas.

In the American South, farmers take out millions of dollars in loans. They use gigantic machines to mechanically pluck, pack and ship their cotton. They can check the price of cotton futures on hand-held computers. But for both "” farmers in the Mississippi Delta and farmers in the African savanna "” the fear of crop failure is constant.

Subsidy Standoff

Seven years ago, cotton farmers from Benin snagged the international spotlight. At international trade talks in Hong Kong, they mounted an unsuccessful attempt to end farm subsidies in the United States that they said were undermining their biggest cash crop.

The 2005 trade negotiations skidded to a halt when trade officials from Benin and three other small West African countries that rely heavily on cotton exports "” Burkina Faso, Chad and Mali "” (known as the "Cotton 4") attempted to make the elimination of U.S. taxpayer subsidies to American cotton farmers a condition for completing trade negotiations.

Since then, the trade talks have been deadlocked.

U.S. subsidies are still in place, but their impact has been muted. Commodity subsidy payments generally kick in during slumps in prices, and international cotton prices for the past two years have been sky-high, holding down subsidy payments to farmers.

However, as cotton producers worldwide have scrambled to cash in on the high demand for their crop, farmers in Benin have been unable to take part in the good times. They've been stymied by a combination of natural forces "” alternating years of flood and drought "” and man-made problems, including corruption and mismanagement.

Bonaventure Kouakanou, an agronomist with Benin's cotton board who is in charge of crop projections, thinks U.S. subsidies have hurt his country's cotton sector. But reflecting on his small nation's experience in the international arena over the past decade, he said Benin is better off focusing inward.

Rather than continuing to press its case on the international stage, Benin has undergone a retooling of its cotton industry.

The government has struggled to shed remnants of the system put in place when it was a French colony, where high-powered groups of ginners and exporters dictated prices to farmers. It has attempted to extract more value from its crops, by adopting new farming techniques and instituting safeguards against opportunists who siphon off government payments to farmers.

"You have to choose what you can resolve," Kouakanou said. "We don't have any power with the United States of America. What we do have is the power to solve problems in Benin."

Unlike many of its West African neighbors, Benin "” which the French colonized at the end of the 1800s "” has not become embroiled in civil war or domestic unrest for much of its modern history. A big reason is that, unlike Sierra Leone, a mining country that crumbled amid more than a decade of civil war that ended in 2002, or Nigeria, Benin's neighbor to the east where a mix of international oil companies and competing armed gangs has created a wasp's nest of crime and corruption, Benin isn't home to vast deposits of oil, gold or diamonds.

Benin is largely a nation of farmers.

In the alluvial plains in its south, where rivers pool into lagoons and eventually pour out into the Gulf of Guinea, rice, pineapples and cashews are the main crops. Farther north, as the thick green vegetation thins and rocky bluffs thrust out of the savanna, cotton dominates.

Benin is one of the poorest nations on earth. Its annual per-capita income in 2010 was $730, according to United Nations statistics. The literacy rate was 42 percent in 2009. Twelve percent of all newborns die before their fifth birthdays.

2005 Trade Talks

As negotiators convened in Hong Kong for trade talks in 2005, members of the Cotton 4 pointed accusatory fingers at the United States "” where, the Africans said, government subsidies prop up cotton producers, allowing them to harvest cotton on the cheap and dump it onto the world market, lowering prices.

Four years earlier, in 2001, when trade officials from around the world met in Doha, Qatar, to lay the groundwork for trade talks, the officials made a clear declaration: Their goal was to end subsidies for crop exporters and drastically reduce all other farm-support payments.

"We agree that special and preferential treatment for developing countries shall be an integral part of all elements of the negotiations," the nations said in Doha, which would give countries like Benin an advantage in future talks.

Early in the past decade, commodity prices dipped, and U.S. subsidies "” including payments to cotton farmers and low-cost loans for foreign buyers of U.S. cotton "” increased.

The international relief organization Oxfam America, citing figures compiled by the International Cotton Advisory Committee, said in a 2002 report that removing U.S. subsidies during the 2001-02 growing season would have raised international prices by 11 cents a pound, or 26 percent.

The subsidies' impact on Benin "” which depends on cotton exports for 40 percent of its gross domestic product (the sum of all of the goods and services it produces annually) "” was a 1.4 percent decline in its gross domestic product and a 9 percent loss of its export earnings, Oxfam America calculated.

Samuel Amehou, then Benin's point man at the World Trade Organization talks, made that case in Hong Kong, but the talks broke down in no small part because of disagreements between the Cotton 4 and the United States and other developed countries that wanted to retain farm subsidies.

The streets of Cotonou "” Benin's major city, whose name comes from a phrase meaning "mouth of the river of death" in Fon, the language of one of the country's major ethnic groups "” are packed tight with motorcycle riders.

Motorcycle exhaust permeates the air. Riders blare their horns and downshift continually as they navigate the traffic. Families of four balancing on motorcycles are a common sight.

Above the din, in an airconditioned office on the top floor of Benin's Foreign Affairs Ministry, Amehou reflected on the stalled talks. "We want to be part of world trade," Amehou said, "but what we produce is cotton, and if the U.S. continues to subsidize cotton, we are finished economically."

Over the past several years, Benin's cotton production has lagged.

During the 2005 growing season, farmers grew 384,000 tons of cotton. Production dipped to 212,000 tons in 2009, and the bottom fell out in 2010, when farmers produced only 158,000 tons.

"Cotton has disappeared from entire regions of Benin," Amehou said.

Though the government has begun to encourage crop diversity, it continues to recognize cotton as an export that produces hard cash, and Benin's government, local cotton experts and international agricultural advisers have worked to professionalize the industry.

To improve the working relationship among cotton growers, ginners and suppliers of pesticides and fertilizers, the government gave the Association Interprofessionelle du Coton "” a privatesector cotton board made up of members of all three groups "” the responsibility of negotiating prices before each season.

The association was given the task of sending out newsletters to farmers in remote villages to give them information about the international price of cotton.

To root out corruption and mismanagement, the association uses Global Positioning System devices to map each farmer's cotton plot and make sure that he receives the correct amounts of fertilizer and pesticide, which are given out on credit. The satellite maps are considered an important tool to document government expenditures and fight mismanagement.

Before the association was created, regional farmer representatives often doled out the supplies without proper oversight, and at the end of the season, charged farmers for more acres than the farmers had dedicated to cotton. Or association agents provided the wrong amounts of supplies or provided them too late to be effective.

And often, farmers used the fertilizers and pesticides on food crops or sold the materials for cash.

Under changes made two years ago, the association stopped working with regional farmer groups that had histories of mismanagement, and fired untrustworthy agents.

Perhaps most importantly, the association and the country's department of agriculture and several international nongovernmental organizations sent thousands of extension agents (from Benin and elsewhere) out into the fields to modernize farming practices and increase cotton yields.

"We've tried to do our domestic homework," Amehou said.

To Market

Wednesdays are market days in Pehunco, a village tucked away in the green hills in north-central Benin.

At her home last fall in Pehunco, Benin, Fai Idrissou spins yarn from cottonseed clumps that fell off trucks during the previous year's harvest. Photo: Alex Daniels

Thousands of people from the surrounding area peruse the food and clothing on display in wooden stalls along the town's main road.

It's late September. The cotton "campaign" "” a Beninese term for the end of the cotton season "” is a few months away, and throughout the area, people are getting ready.

Up a windy road on a hill above the town center, Fai Idrissou folds her delicate frame onto her working mat in a corner of her square, crudely-built hut. Deeply wrinkled, she won't say how old she is. She and her family live without electricity in the village where her people, who speak a dialect called Bariba, cook food on a wood-fueled fire in the middle of a dirt yard.

Each December, when the cotton trucks lurch along the town's potholed roads, stray cotton seeds spill out. Idrissou walks along the ditches and gathers the stray seeds, each surrounded by a clutch of cotton fiber.

Idrissou is down to her final bag of last year's seeds. On the mat, she pulls a clump of fiber and winds it on a 9-inch wooden needle. The needle has a knobby ball on the bottom, which is coated with a chalky bone meal to reduce friction. The ball rotates on a wooden board, as she spins the cotton off the seed, she stretches it into string that she winds around the needle.

It takes two months and six spools of the string to make enough yarn for a dress.

"It requires patience," she says. She will net less than $1 per spool.

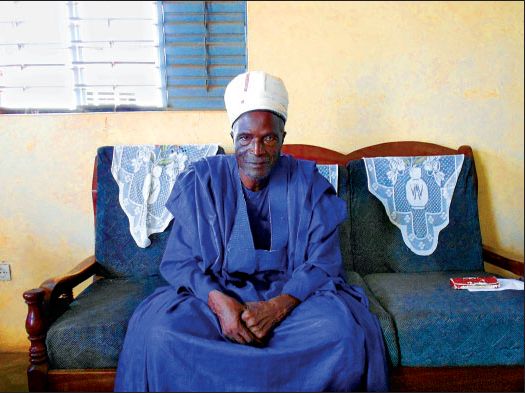

King Kpei Sourou, Pehunco's traditional monarch, lives in a compound off of the town's main square. The dirt courtyard of his palace is strewn with old bicycles, tires, firewood and a rustedout tractor.

Sitting on a couch in his sparse reception area, he tells a visitor about the big changes that came in 1968. That's when Peace Corps volunteers from America introduced the kingdom to the use of oxen in cotton cultivation.

Pehunco's 55,000 people seek the monarch's judgment in land disputes or his advice when family members are in poor health.

These days, the king is worried because cotton yields are down and the local economy is stagnating.

"I see my children leaving the kingdom to find work," he says. "It pains me, but I am the father. I must stay here."

Kpei Sourou, the monarch of Pehunco "” a legally recognized kingdom in Benin "” greets a visitor in his reception area.Photo: Alex Daniels

About 2 miles from the king's palace, members of the Fulani ethnic group have parked about 100 of their motorbikes in a clearing. They've gathered there for a livestock auction.

One man carries some scrawny chickens, a dozen at a time, and walks from the center of the activity to his motorcycle, where he eases the birds into a conical strawcarrying case, attaches it to his bike and rides away.

Others, with green tattoo markings on their faces, inspect tethered oxen.

A few miles farther up the dirt road, Jean Albert Houessou sits behind his desk and grimaces. He has a touch of malaria, but this manager of the town's cotton gin has bigger worries.

Over the past several years, the cotton crop hasn't kept his gin busy enough.

Houessou "” a neat man in his 30s who wears pleated khaki pants and a button-down oxford shirt with cuff links "” seeks comfort in his air-conditioned office as some of his 25 full-time workers get ready for the coming campaign.

The gin's intake pipes, which usually hang vertically at the plant's front door and are used to suck cotton out of trucks, have been dismantled and lie on the ground, awaiting inspection. Discarded cotton lint from last year's harvest litters the building's floor in little clumps around the idle gin.

During the cotton campaign, when he needs extra muscle and additional mechanics and electricians to run the gin, Houessou's staff balloons to 200.

The gin has not operated at its capacity of 25,000 tons per season since 2006. That year, the plant pressed and sifted at nearly full tilt, separating 22,805 tons of cotton from its seeds. Last year, the gin's output was 13,241 tons.

Houessou says he needs more cotton to pay his seasonal staff and to buy oil to run the plant. Benin's national electric grid is not powerful enough to keep things going, so the plant uses a generator. Houessou says it costs 2 million Central African francs, or about $4,000 a day, to keep the plant going.

On a few acres just outside the plant, cotton bolls are opening, showing their white. The cotton was planted earlier than cotton grown on area farms, where white and purplish flowers are just beginning to bloom.

The plot was planted to give Houessou an idea of when the gin needs to be primed and ready for the rush of crop-laden trucks.

"This year, I think we'll have double the yield," he said, scanning the field.

He's optimistic because governmental changes in the cotton sector have begun to take hold.

But others see too much focus being put on one crop.

Soule Manigui, program officer at CTB-Benin, a Belgian nonprofit that works to alleviate hunger, says Benin's "cotton craze" has led farmers to plant cotton instead of food, creating shortages in parts of the nation.

"We need to develop other crops," Manigui said.

Since the Cotton 4's push in the world trade talks, there have been signs that Benin's government is routing resources usually reserved for cotton to other crops.

In 2009, the government began supplying fertilizer, pesticides and seeds for other crops on credit, something it had previously done only for cotton. As a result, acreage for crops like corn, cassava and cashews has increased.

But cotton continues to be Benin's primary crop.

Manigui points out that after Benin's thin cotton harvests two years ago, President Boni Yayi purged the agriculture ministry, placing Sabai Kate as head of the department. Kate is the former mayor of Banikaora in the country's northern savanna in the heart of cotton country.

Manigui sees one reason for putting Kate on the job: "He's there for cotton."

Steps Taken

Assisting Kate are 2,000 agriculture ministry extension agents. They join 570 agents from the Association Interprofessionelle du Coton and thousands more from nonprofits, including the West African Cotton Improvement Program "” a project funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development "” and Cotton made in Africa, a project run by a consortium of nonprofits, businesses and the German international development agency GIZ.

Alex Daniels, a reporter for the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, stands to the left of cotton farmer Sero Yerima, in the rust-colored suit, and other villagers last fall in Pehunco, Benin. Photo: Alex Daniels

Horst Obel, a cotton expert with GIZ, trains 200 Beninese farming agents, who in turn lend their crop expertise to 2,000 model farmers in the Pehunco region.

By teaching precision farming, including techniques for determining how much pesticide to spray and when, Obel said, farmers can cut their pesticide costs in half and need up to 40 percent less fertilizer, cutting down their overall costs and improving environmental conditions.

This year, the Association Interprofessionelle du Coton set the price paid for cotton at 250,000 Central African francs per ton, the equivalent of $508.

At the peak of the cotton market last year, a ton could have been sold for more than $2,000 on the international market.

Last year, in response to the advice he's gotten from the West African Cotton Improvement Program and historically high cotton prices set by the Association Interprofessionelle du Coton, Sero increased "” for the first time in his life "” the amount of land he set aside for cotton. Instead of dedicating about 20 acres to cotton, he planted roughly 30 acres.

Others increased their cotton acreage, too, resulting in a production yield jump of about 300,000 tons. That's still well below the 2005 yield but an improvement over the years since.

Standing next to his grandmother's grave in his cotton field, Sero says he has no idea what cotton sells for on the international market, but the $508 he's been promised looks pretty good.

"It gave me the motivation to work hard."

Alex Daniels reported from Benin with a grant from the International Reporting Project (IRP).

More from this Reporter

- Batesville to Benin: West African Preaching School Helped by Southern Churches

- Cotton Growers in Limbo

- With No Money to Fight U.S., 4 Took Cotton Case to WTO

- Beninese Scrape by on Average of $730 a Year

- From Benin to Arkansas

- In Benin, Genetically Modified Cotton Not Option for Now

From Other Reporters in This Country

Also appeared in…

- Arkansas Democrat-Gazette