Batesville to Benin: West African Preaching School Helped by Southern Churches

In the land of Vodun, a form of spirit veneration more popularly known in the West as Voodoo, religion is an essential facet of life.

George Akpabli, a Church of Christ minister who runs a preacher training academy in the countryside outside of Cotonou, says religious enthusiasm is a hallmark of Benin, regardless of which god is being worshipped.

"Beninese are religious right from birth," says Akpabli, who built his school with the help of more than $100,000 in donations from North Heights Church of Christ in Batesville. "I don't think there are any atheists in Benin."

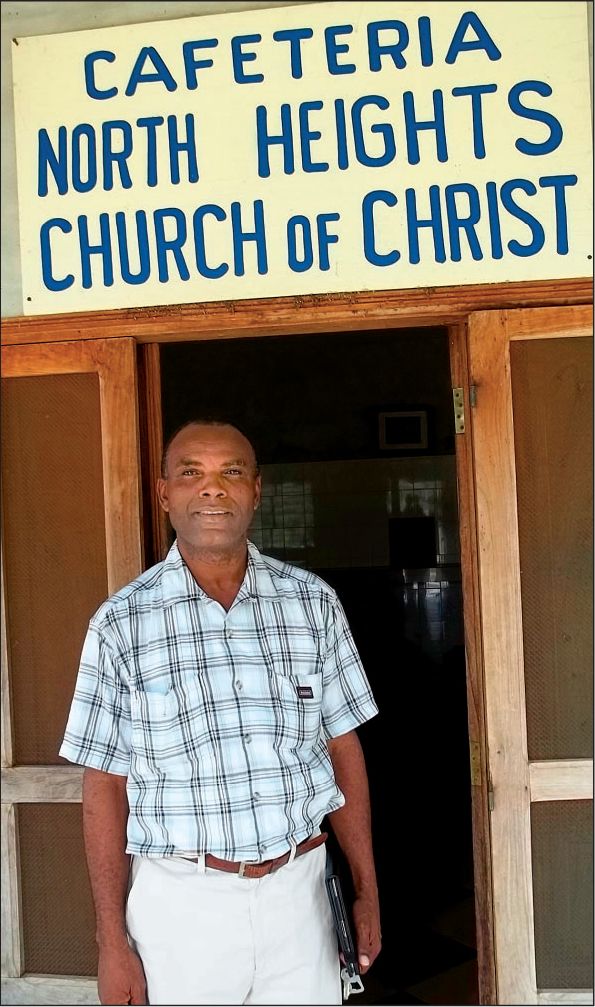

George Akpabli poses outside a cafeteria on the campus of his Cotonou, Benin, preacher training academy that is named after North Heights Church of Christ in Batesville. The congregation donated more than $100,000 to help pay for the building.Photo: Alex Daniels

That enthusiasm was put on display last fall when Pope Benedict XVI visited the country and was cheered by thousands of admirers in the heavily Catholic country.

During his visit, Benedict signed a "Post-Synodal Apostolic Exhortation" that called upon Christians in Africa to "be a witness in the service of reconciliation, justice and peace."

And the zeal manifests itself in the dedication and sacrifice of some of the 35 students who travel from throughout West Africa to Akpabli's school each year.

Akpabli, who was born in Ghana, moved to Benin in 1993. He approached Benton Church of Christ in Kentucky for a donation. With an initial gift of $3,500, he bought furniture and rented an apartment in Cotonou, where he held Bible classes.

Now, 19 years later, Akpabli's school and a related group, the French African Christian Education Foundation, have raised more than $700,000 and moved to an 18-acre campus in the countryside.

"It was just a dream," Akpabli says. "I didn't know it would take off."

Churches of Christ in the United States have embraced Akpabli's ministry. In 2010, he traveled to Kentucky and Arkansas to preach and meet with church leaders.

So far, 135 students have graduated from Akpabli's three-year program. In addition to courses on theology, Scripture and logic, the school offers vocational courses on agriculture and plans courses in carpentry and computer engineering.

Comforts on the school's campus are a step above most rural villages in Benin. Underground electric cables channel electricity from the grid to the school's nine or so buildings. A backup generator provides electricity during the regular power failures.

The students and their 12 instructors grow carrots and beans in irrigated gardens. Lizards dart through the fields. Outdoor sheds hold dozens of rabbits and pigs.

In bold blue lettering, a painted sign above the school's cafeteria reads "North Heights Church of Christ," in honor of the Batesville church. The 350 or so members of the Arkansas congregation donated about $100,000 for the construction of the school's mess hall.

George Akpabli points to a framed photo of Church of Christ friends from Arkansas who helped him build his dream "” an 18-acre Bible school. Arkansans sometimes visit the campus and Akpabli has traveled to the state to preach. Photo: Alex Daniels

Inside hangs a photo of four of the church's elders, Jim Williams, Ronnie Dowdy, Tom Tackett and Bill Martin, taken in 2002.

That's when the church first began taking a special monthly collection to donate money to the African school.

Tim Bruner, one of the church's current elders, said the church's 10-year association with the Benin school grew largely because of the enthusiastic reception Akpabli's school got among the Beninese.

"The fields are white unto harvest," he said, referring to a passage from John's Gospel.

"You have people hungry for knowing about something else," Bruner said. "If they're going to listen and respond, let's keep feeding that desire."

Antoine Fassa Tolno, a 47-year-old preacher from the West African nation of Guinea, arrived at the school in early October and was just getting settled in his dormitory as Akpabli readied campus for the academic year.

Born Catholic, Tolno said he came to the school so he could better spread the word of God in his native country.

"The promise of the New Testament is that you must be saved through Jesus Christ," he said. "And before being saved, you have to have love in your heart. You have to live righteously."

Christianity is just one of the religions competing for the faith of the Beninese.

According to a 2002 census, 48 percent of the country identified as Christian, with Catholics making up 27 percent of the total. Muslims accounted for 24 percent of the population, and Vodun practitioners 17 percent. The remainder identified as "other."

Akpabli insists that the Beninese practice their religion with a minimum of tension.

He says: "My lawyer is Muslim, and he prays for me."

But he says he does experience some friction from Vodun practitioners.

"People believe there are spirits who control your life from birth to death. Sometimes that spirit can be displaced by a spirit that is stronger. We say that putting your faith in mountains and stones is ridiculous. We try to remove those intermediaries. There is a higher power."

Practitioners of Vodun, a form of spirit worship that originated in southern Benin, emphasize ancestor worship and pray to Vodun, or spirits, that are rooted in the natural world.

When the pope exhorted Benin Catholics, he did so in Ouidah, a coastal town in the south that is the center of Vodun life and tradition.

Tim Landry, who was initiated into the Vodun system in Haiti and then as a Fulbright Scholar in Benin in 2009, said many in Benin, regardless of what religion they outwardly profess, are adherents of Vodun.

For instance, he said that he knows an evangelical Christian in Benin who considers Jesus her Vodun. And, he said, as a "cover all your bases kind of thing," some Beninese go to church on Sunday, then go to Vodun priests during the week asking for ritual protection.

Passages in the Old and New Testament about witches and devils and demons are not dismissed.

"There's not a single Christian in Benin who does not believe in witchcraft and the power of sorcery," he said. "Religious systems in West Africa don't have rigid boundaries. If people see something of value in an other religion, they'll utilize it."

Bruner, the elder at the Batesville church, said everyone in his congregation "was sold" on Akpabli because he was a great educator and could communicate in French and West African dialects with students.

Also, trips made by church members to Benin and by Akpabli to Arkansas solidified the bond.

"Underneath everything there is a relationship," Bruner said. "That relationship has been cultivated and nurtured over the years."

Alex Daniels reported from Benin on a grant from the International Reporting Project (IRP).

More from this Reporter

- Cotton Growers in Limbo

- With No Money to Fight U.S., 4 Took Cotton Case to WTO

- In Tiny Benin, Cotton Is King

- Beninese Scrape by on Average of $730 a Year

- From Benin to Arkansas

- In Benin, Genetically Modified Cotton Not Option for Now

From Other Reporters in This Country

Also appeared in…

- Arkansas Democrat-Gazette