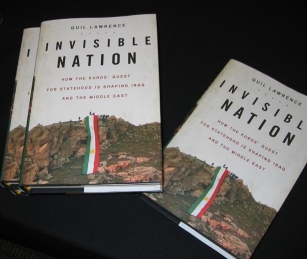

“Invisible Nation: How the Kurds’ Quest for Statehood is Shaping Iraq and the Middle East”

Q&A; with Quil Lawrence

Quil Lawrence is a Middle East Correspondent for BBC/PRI’s “The World” and a former IRP Fellow. He’s reported extensively from Iraq, traveling to every major city and reporting from all the neighboring countries. He covered the assault on Fallujah and all of Iraq’s elections. He is the author of the new book “Invisible Nation: How the Kurds Quest for Statehood is Shaping Iraq and the Middle East.”

Q: You first wrote about the Kurds when you were an IRP Fellow in 2000. What got you interested in the Kurds at that time?

A: In 1999, the leader of the Turkish militant group the PKK got arrested and when he was thrown in jail Kurds all across Europe, Kurdistan and other regions were so upset that they set themselves on fire. These self immolations made headlines all over the world. I was intrigued about what would make someone do that, the power of the ethnicity and nationalism that drove people to such an extreme measure. I looked into it and the IRP fellowship was a good fit; it was an uncovered, unknown corner of the world in the news.

Q: Did you know then that you would stay with this story for so long?

A: Not really. I got on a couple of informational mailing lists and kept tabs on Iraq after my fellowship and then 9/11 happened. Although Iraq was not involved, there were a lot of speculation about Al Qaeda groups in Northern Iraq and Kurdistan. Suddenly my IRP Fellowship turned into the most incredible preparation anyone had ever unwittingly done.

Q: What motivated you to write this book now?

A: I thought that the Kurdish issue was still not properly covered [or] understood by Americans. There were a few other people who were writing books about the region or who I thought would write about Kurdistan and do what I meant to do, which is explain the Kurdish factor in Iraq to an American audience. But no one did. There was a space for this book in the market and an empty spot in the literature about Iraq.

Q: What are some of the common misperceptions about Kurds?

A: I’m not sure if there are any perceptions, much less misperceptions, among Americans. It’s hard for Americans to even categorize them. They’re Muslims, but not Arabs, they’re not Turks; they’re really not anything anybody has really heard of. American diplomats and politicians that go to Baghdad usually only hear an Arab perspective. If you have someone in the U.S. government that speaks a Middle Eastern language it’s probably Arabic, maybe Farsi, but never Kurdish. People don’t know too much about them.

Q: There are Kurdish communities in many countries in the region: Turkey, Iraq, Iran, and Syria. How are they different, or similar, and how much do they have to do with each other?

A: They’re connected, but separated by language barriers and political boundaries. What they have in common is the persecution that binds them. You see Syrian Kurds coming across because in their own country they are non-persons, they have no documents. Iranian Kurds go to Iraqi Kurdistan for the free education and many of them will openly say that they will use it to overthrow their own government. The biggest geographic and linguistic divide is between the Turkish Kurds and Kurds in other countries. Relatively speaking, the Kurds in Turkey are prosperous, although within Turkey they are among the most down trodden. Compared to Kurds in Syria, Iran and Iraq, they are so far ahead it is difficult seeing them wanting to join up to a greater Kurdistan.

Q: Your focus in the book is on the two main Kurdish political parties, the PUK and the KDP; they've been divided for years. Do you see this as a permanent divide?

A: They’re trying to come together and make it more of a divide like the Democrats and Republicans in the United States, as opposed to a civil war, which they had in the 1990’s. Today you see representation from both sides in Washington and they work together very well. They know that they can’t wipe each other out militarily. Republicans and Democrats are a division that began in the U.S. Civil War, hopefully Kurdistan is along the same path. Maybe they’ll be bitterly divided, they’ll snipe at each other, but they’ll also keep each other honest.

Q: Why do you feel it's important that Americans know about the Kurds?

A: You can’t really understand what’s going on in Iraq ignoring 20 percent of the population and one of the three main players: the Kurds, Shiites, and Sunnis. People need to know about the Kurdish role, especially because it’s been a disproportionately large role. America helped set up a Kurdish safe zone in 1991 and then the Kurds had a dozen years to grow up offstage where no one was watching. They’re politically more mature than the rest of Iraq and the economy is more developed in some ways. Today, it’s the only place you can go safely in Iraq. People should know that if the U.S. pulls out without taking care of the Kurds, they’ll be setting this adrift. They should know what it is that they are hanging out to dry.

Q: How would you characterize US foreign policy towards the Kurds?

A: With the souring of relations with Turkey, by default, it became very good for a little while. America really needed the Kurds. They are still the only unambiguously pro-American faction, both their leadership and population, in Iraq. Unfortunately, Kurdistan is viewed as the quiet spinning wheel that gets no grease. It’s the squeaky wheels of Sunni Arab Iraq in the south that gets much of the reconstruction money. From a Kurds perspective they should be viewed as a success story that should be reinforced, a safe place to invest and rebuild. In Kurdistan you can put up a new building with copper wiring and no one will come along and rip the wiring out to sell it for scrap. In a way the Kurds feel they have been a victim of their own success because things aren’t so urgent up there, they are not getting what they need like electricity and water sanitation. This summer there will be blackouts and brownouts in Northern Iraq and Kurdistan.

Q: When and how do you think the war in Iraq will end?

A: No idea. Some people fear that if the U.S. pulls out there will be a civil war that turns into a regional war, killing half a million people. If the U.S. stays there will probably continue to be civil strife, and a low level civil war that will kill many people. We can end up ten years from now finally having a government in Baghdad and federal system in Iraq and look back saying what a disaster, a hundred thousand people died over this long civil war. Maybe that’ll be the best case scenario. We just don’t know. History will not reveal which options saves lives or is better. The fact is that there is no good solution.