Cloud of Political Scandal Over Ukraine

Internet journalist who was thorn in President Kuchma's side disappears

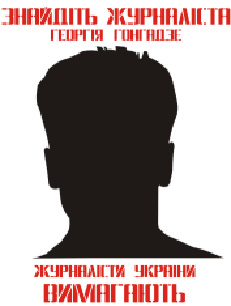

Image used in Ukrainian newspapers to symbolize the missing journalist.

Kiev, UKRAINE, December 14, 2000 -- As Ukrainian authorities prepare to shut down the Chernobyl nuclear plant's last functioning reactor at a ceremony tomorrow, it's not radiation but political scandal that hangs over this former Soviet republic.

Ukraine is reeling from a grisly chain of events involving a missing journalist, a headless corpse, hidden microphones and accusations of criminal activity on the part of President Leonid Kuchma.

The scandal began the night of Sept. 16, when Internet news site founder Georgiy Gongadze, 31, disappeared.

Gongadze had been an outspoken critic of Kuchma and his close associates, and his cyberspace venture, Ukrainian Truth (http://www.pravda.com.ua) published a steady stream of articles about the country's oligarchs -- men such as former Prime Minister Pavel Lazarenko.

Like many other tycoons and Kuchma himself, Lazarenko comes from the ranks of former Communist Party bosses in Ukraine's industrialized east. He accrued his wealth, critics say, off the trading of oil and gas contracts in Ukraine while pocketing millions meant to be invested in the country's ailing energy sector.

Lazarenko is now on trial in federal court in San Francisco, charged with laundering $114 million of his nation's money and using it to buy, among other things, a Marin County mansion once occupied by actor Eddie Murphy.

Gongadze wrote frequently of high-level corruption and urged readers to be skeptical about the claims of their elected leaders -- not much of a stretch in a country where the economy is virtually prostrate and little progress has made toward an open democratic system.

"Remember the speeches of (former Communist Party Chairman Leonid) Brezhnev about the achievements of the Soviet economy and the rising level of the welfare of our fellow countrymen?" Gongadze wrote in an editorial last April. "Ask yourself if you believe the words of the present leaders of Ukraine about our soon-to-be improving quality of life, economic growth, justice and anything else."

Press freedom is rare in Ukraine, said Anders Aslund, a senior associate at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and a former economic adviser to the Ukrainian government.

"The media is the worst part of Ukrainian society today," he said. "The newspapers have essentially ceased to be newspapers and have become leaflets of a few major oligarchs" who also own controlling shares in the country's television and radio stations.

This year, the Committee to Protect Journalists, in New York, placed Kuchma among its top 10 "Enemies of the Press" worldwide, citing incidents of violence and bureaucratic harassment leading up to the 1999 elections in which he won his second term.

Aslund and others see the Internet as one chink in the informational armor, but in a nation where the majority earn little more than $2,000 a year, Web access is unaffordable for most of the more than 50 million people.

Gongadze's co-editor, Olena Prytula, thinks Ukrainian Truth's real-time reportage has stuck in the craw of leaders still accustomed to Soviet-style journalism that merely parroted government positions.

"It's not like we uncover new information, it's just that we nip them every time they do something wrong." she said. "It's the kind of criticism that people are not used to in this country."

When Gongadze disappeared, Prytula and other journalists feared he had been murdered, probably in retaliation for his writings.

Those fears turned to certainty in mid-November, when Prytula decided to investigate an unidentified corpse found in the woods about 90 miles from Kiev.

The decapitated body had been sitting in an unrefrigerated rural morgue for two weeks.

Jewelry found with the body matched that worn by Gongadze, but Prytula says the clincher was a shrapnel scar in the left wrist. Gongadze had a scar in the same spot, and Prytula shows visitors the coroner's X-ray as proof the corpse is that of her onetime colleague.

But before Prytula could claim the body, Kiev authorities snatched it from the morgue. The Ministry of Internal Affairs said the body would undergo an autopsy, but only in the past few days have officials announced an attempt at identification through DNA testing.

The story had faded from the front pages until Nov. 28, when Olexander Moroz, leader of Ukraine's Socialist Party and a rival of Kuchma's, released a recording he said was given to him by a member of the president's security service. On it, a voice similar to Kuchma's is heard to curse Gongadze and other opposition journalists.

"I'm telling you, drive him out, throw him out," the voice says. "Give him to the Chechens."

Although the poor-quality recordings have yet to be authenticated, they caused an immediate uproar. Kuchma acknowledged as much in a speech to the nation last week. He blamed the scandal on people who want to destabilize the country, calling the affair "a provocation aimed at depicting Ukraine as an uncivilized, savage and dark state."

Yesterday, with pressure continuing to build, Kuchma strongly denied that he had issued orders for any violent measures to be taken, and for the first time he called the audiotapes a fake.

Three opposition lawmakers, sensing Kuchma's vulnerability, traveled to Europe last week to interview the officer who says he made the tapes, and who is now in hiding.

Mykola Melnychenko told the parliamentarians that he heard Kuchma give orders to top ministers "aimed at the elimination of opposition media which did not please (his) regime" -- and that Kuchma also wanted to "muffle" Western news services such as Radio Liberty and the BBC.

Melnychenko said he had gotten so fed up with what he heard emanating from Kuchma's offices that he decided to hide a digital recorder in a couch in the president's office.

"I swore an oath to Ukraine and the Ukrainian people," Melnychenko said in a videotaped interview. "I did not swear an oath to Kuchma that I would carry out his criminal orders."

The parliament listened to the interview in a stormy session Tuesday, as members of Kuchma's Cabinet endured shouts of "Murderer!" and calls for their resignation.

If the voice on tape proves to be that of Kuchma, Adrian Karatnycky, president of Freedom House, a pro-democracy nongovernmental organization with offices in Ukraine, wonders why the president would be so bothered by a relatively small-time Internet journalist:

"That's one of the great tragedies. Here's a guy who was twice elected, yet he had the mentality that even the smallest criticism and the smallest opposition group constituted a major threat that had to be dealt with, impeded and harassed."

Karatnycky believes the parliament could muster the vote for an impeachment trial, although it's not clear whether Ukrainian law -- only 9 years old -- offers any guidance on how to proceed. Others fear that Kuchma could bypass parliament by declaring a state of emergency, effectively sending the country down the path of more authoritarian neighbors like Belarus.

Despite those dangers, Karatnycky says the shakeup could do Ukraine good.

"You have the beginnings of some checks and balances, the beginning of some sense of self-respect among government officials," he said. "And I don't think anyone's cowering in fear."